|

5 Men Leave Guantánamo for a Bleak,

Uncertain Future

By NEIL A. LEWIS

New York Times

WASHINGTON, Aug. 14 — Early on May 5, five Asian

men who had been detained at the prison camp in

Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for years as dangerous

terrorists, boarded a military transport plane at the

United States naval base there.

The men had just exchanged their prison garb for jeans,

T-shirts and slip-on sneakers but were still in

handcuffs as they boarded the plane, where they were

shackled to bolts in the floor and surrounded by more

than 20 armed soldiers. About 14 hours later, the

plane landed in Albania, a poor Balkan nation eager to

please Washington.

Interviews with lawyers and several officials in the

United States and abroad showed that the flight, to a

freedom of sorts for the five men, involved intense

behind-the-scenes diplomatic activity in Washington;

Ottawa; Tirana, Albania; Beijing; and elsewhere.

It also held implications for a United States Appeals

Court, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the

relations of several European countries with China.

And it underlined the Bush administration’s

difficulties in reducing the population at Guantánamo

as international calls for it to be closed increased.

The five men were Uighurs (pronounced WEE-gers) who

had been captured in Afghanistan after the Sept. 11,

2001, attacks. They had traveled there from their

homeland in the Xinjiang province of China, where the

Uighur people, most of whom are Muslims, have fought a

low-level insurgency against Beijing’s rule for years.

For the five Uighurs, the transfer to Albania meant

exchanging a military prison camp on the southeastern

tip of Cuba for a bleak and unpromising future in one

of Europe’s poorest countries where no one spoke their

language. One of them, Abu Bakker Qassim, said in an

interview, “I would rather be in a society where I can

be with some of my countrymen, but where we are is

better than Guantánamo.”

For the Bush administration, one of the immediate

results of the transfer was an opportunity to sidestep

yet another court challenge to its detention policies.

Shortly after the five men landed in Tirana, Albania’s

capital and largest city, and only minutes before the

close of business in Washington on a Friday, the

Justice Department filed a brief with a federal

appeals court there. The brief asked the court to

cancel a hearing the next Monday on the Uighurs’

challenge to their continued detention in Guantánamo

Bay. They had been held there for more than a year

after the military’s special tribunal system had

determined they were not “enemy combatants,” the

ostensible reason for their imprisonment.

A federal judge had ruled that the Uighurs’ continued

detention at Guantánamo was illegal and disgraceful,

but he said he could not order them admitted to the

United States, as their lawyers had requested. The

appeals court was considering that issue. The Bush

administration has opposed allowing Guantánamo

detainees into the United States.

Upon learning the Uighurs were no longer at Guantánamo,

the appeals court canceled the hearing.

A senior State Department official said in an

interview that more than 100 countries had been

approached about accepting the Uighurs but that only

Albania did. Even though they were innocent, the

official said, the five Uighurs could not be

repatriated to China because Beijing regarded them as

terrorists, and the law prohibited sending prisoners

to places where they might be persecuted.

The countries that declined, including Washington’s

best European allies, did not want to antagonize

China, officials and analysts said.

The State Department official said the timing of their

departure and the scheduled court argument was a

coincidence. But a senior Justice Department official

said there had been an intense push to avoid a

situation in which the appeals court could order the

Uighurs admitted into the United States. Both

officials spoke on condition of anonymity because of

the delicacy of diplomatic relations.

For Albania, the willingness to accept the Uighurs

solidified that nation’s standing with the United

States and brought it a confrontation with China,

which had been its patron during Albania’s split from

the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

On the weekend of the Uighurs’ arrival in Tirana, the

Chinese ambassador there protested to the Albanian

prime minister, insisting they be returned to China.

The ambassador repeated the demand on Monday.

But the following day, May 7, Vice President Dick

Cheney publicly endorsed Albania’s much-hoped-for bid

to join NATO. Charles Gati, an authority on Eastern

Europe and a professor of European studies at the

Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of

Johns Hopkins University, said that Albania had

courted Washington in recent years.

“They’re very eager to get into NATO, and to do this

they have offered their services in a variety of ways,”

Professor Gati said. “This is clearly what happened

here.”

Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha, who was at Mr.

Cheney’s side when he announced United States support

for Albania’s NATO bid, along with the bids of Croatia

and Macedonia, said in a statement later that week

that he trusted Washington’s assurances that the men

were not terrorists and that he was proud to provide a

humanitarian favor to Washington.

China remained unappeased and seemingly went beyond

diplomatic pronouncements. In the first week of June,

a Chinese delegation arrived unannounced at the

barbed-wire-enclosed refugee camp on the outskirts of

Tirana and demanded access to the Uighurs. Their

intentions were unclear, but Albanian officials denied

them entry.

Early this month, the Albanian government granted

asylum to the Uighurs. The Albanian ambassador to

Washington, Aleksander Sallabanda, said in a statement,

“Our government is proud of its cooperation with the

United States in the war on terror.”

For the five Uighurs, the consequences of the move to

Albania were more prosaic and dispiriting. At the time

of their transfer, their lawyers had been making

progress in negotiating with the Canadian government

for them to settle there. Canada has a thriving Uighur

community, largely in Toronto.

But that possibility stalled when they were sent to

Albania, their lawyers said.

More than 100 prisoners at Guantánamo were initially

found to be enemy combatants and then ruled eligible

to be freed but were not because it was impracticable

to return them to their home countries, and no other

country would accept them.

That group includes a few other Uighur prisoners at

Guantánamo who have not been transferred to Albania

because, their lawyers say, they have no scheduled

court argument that the administration hopes to avoid.

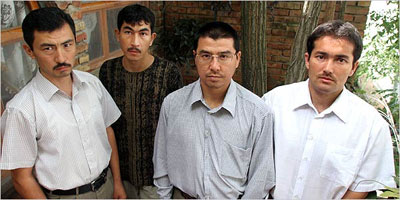

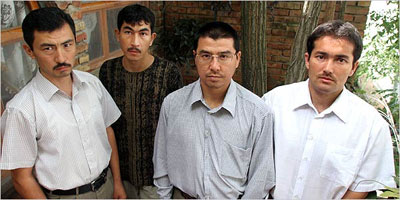

The freed Uighurs now spend most of their days in the

refugee camp in a poor slum of Tirana, according to

Sabin Willett, a lawyer in Boston who represents two

of the men. Mr. Willett said he had learned of the

transfer only after it happened, and he went to Tirana

that Monday.

Michael Sternhell, a New York lawyer who represents

the other three Uighurs, said the men “are still

effectively behind bars.” Mr. Sternhell says they have

difficulty even traveling to the center of Tirana, and

they use most of their monthly allowance of 40 Euros

to call their families in China. The Albanian

government provides room and meals at the center, for

which it is reimbursed by the United States.

Although the Uighurs feel marooned in Albania, they

are grateful to the government there. “Given that no

other country is taking us, we’re all right with this,”

said Mr. Qassim, a 37-year-old father of four who acts

as the group’s spokesman. Speaking by telephone from

the refugee center through a translator retained by

The New York Times, Mr. Qassim said that the problems

had begun when he and several fellow Uighurs had left

their home to find a place to study the Koran, a

practice he said was forbidden in China.

They went to Pakistan and then to Jalalabad,

Afghanistan, he said. After the Sept. 11 attacks, a

group of 17 Uighurs returned to Pakistan, where local

tribesmen welcomed them warmly. After a lamb feast,

the villagers betrayed them. They were taken to a

mosque ostensibly to worship, but instead, Mr. Qassim

and his lawyers said, they were sold to United States

forces.

According to the transcripts of tribunals held at

Guantánamo, they were accused of engaging in guerrilla

training, but officials would not tell them on what

basis they had made the accusations because the

information was classified. Mr. Qassim said the

Uighurs had indeed learned to use rifles while in

Jalalabad, but he said weapons training was common in

Afghanistan, and he had never heard of Osama bin Laden

or Al Qaeda.

Mr. Qassim and the four other men who would wind up in

Albania were deemed not to have been enemy combatants.

The 12 others in their group were classified as such.

“It’s a mystery as to why we were released and the

others are still languishing behind bars,” he said. He

said the United States had made a “mistake” in

believing the Uighurs were radical Islamists opposed

to the United States. Mr. Qassim said his people had

always admired the United States and had hoped that

one day America would rally to the Uighurs’ cause for

freedom.

“We still believe the U.S. is a good country with good

people,” he said. “But the government has made a

mistake and is still making it.”

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company

|