|

|

|

Freedom, Independence and Democracy for East Turkistan ! |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

E-mail: etic@uygur.org |

|||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

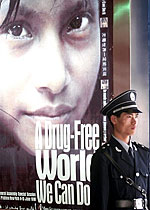

Growing Heroin Trade Hits Uyghurs in China's Northwest

“This year, there are more. We arrested a total of 70 drug addicts. Forty of the drug addicts were sent to the White House compulsory rehab center in Urumqi,” he added.

Experts say heroin from Burma started showing up in Xinjiang in 1994. Initially, Uyghurs smoked it, but recently they have begun injecting it, creating a major AIDS crisis in the region, Justin Rudelson, executive director of the Institute for Global Chinese Affairs at the University of Maryland, told a 2002 U.S. congressional hearing on China. “Within a drastically short time, Xinjiang has emerged as China's most seriously affected region and the Uyghurs are the most affected of all of China's peoples,” Rudelson said. One Uyghur woman from Xinjiang, who asked that her name and location not be disclosed, described the effects of her husband’s heroin habit on their family. Drug habit spreads“My husband takes that stuff and injects it. He takes my motorbike and brings it back. I cannot afford to take care of my children well now,” she told RFA reporter Guljekre. “He takes the money whenever there is some money and he also takes the things from home [to sell]. He quits for a while and goes back to it again,” she said. “We used to have a shop and now it is closed. He stays at home and waits for me to bring food home. People find ways to get drugs and take drugs and they get it from each other. He spends his days crying. He cries every day,” she said. “We cannot find any other way to help him, and we're just waiting for him to die. To get stoned and die. People get stoned and die often,” she said. A police officer in Maralbeshi county in the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan, on the trafficking route between Burma and Xinjiang, admitted that the authorities were doing little to attack the root of the problem by stemming the supply to the northwest in the first place. Asked if they only acted at the tail end of the supply line, the officer said: "That is right. They are not doing as you suggested [stopping it from getting to Xinjiang]. Over here, we normally do rehabilitation. And we also punish those who are selling the drugs openly. That is the solution now." Beijing blamedHe said those caught using drugs were sent for "re-education through labor", an administrative sentence of up to three years which can be imposed by police without need for a trial. A member of staff at the Urumqi Voluntary Drugs Treatment Center told RFA that the center charged 2,350 yuan (U.S.$293) for a 10-day rehab program, and that those sent to the mandatory rehab center were also charged fees for treatment. “This is a volunteer place and people come here voluntarily to quit drugs,” the official at the government-run clinic said. “On the other hand, the others are mandatory, and you still have to pay after you are released from them…In fact, the [treatment center] is a jail.” Sources told RFA’s Uyghur service that rehab programs rarely worked because they couldn’t afford methadone, a heroin substitute commonly used in clinics elsewhere. “We’ve got quite a lot of returning patients,” the rehab clinic official said. “It’s all up to them after they are released from here.” Low levels of educationMany Uyghurs, who twice enjoyed short-lived independence as the state of East Turkestan during the 1930s and 40s, are bitterly opposed to Beijing’s rule in Xinjiang. They see the growing drugs and AIDS epidemic as part of China’s colonial rule in the region. Former drug-trafficking enforcement officer Behtiyar echoed the concerns of many Uyghurs who spoke to RFA that the Chinese authorities weren’t trying as hard as they might to address the problem. “A nation can be destroyed in many different ways,” said Behtiyar, who is currently living in the Netherlands. He said corrupt government officials were frequently a part of the increasingly professionalized trade in opiates from the Golden Triangle. “Drug abuse is common in other parts of China, and the government is quite successful in drug-trafficking,” he said. Beijing links drugs, terrorHe blamed low levels of education and development among Uyghurs for their vulnerability to the drugs trade. “First of all, our people are living in backwardness. They are not getting the education they need. Furthermore, our people cannot practice their cultural and religious beliefs, and they are being forced to do certain things against their will. Therefore, they are into drugs now.” “Secondly…our people are living in poverty and hunger. They hardly have much income to live on and they have no other ways to support themselves,” he added. An article published online by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Silk Road Studies in February said heroin retail prices were currently 4-5 times higher in Xinjiang than in the Central Asian countries it borders, and that the province “has a sizeable and growing drug addict population.” “The primary supplier to this market has been Myanmar [Burma] via lengthy routes across China, but the logistical challenges to Central Asian suppliers are diminishing quickly,” wrote author Jacob Townsend. Chinese authorities have linked the war on drugs to their own "war on terror" in Xinjiang, where Beijing claims that terrorist organizations operate, some with links to al-Qaeda. Top officials first began linking the issues of terrorism and drug-trafficking at a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2004, launching a campaign more defined by ethnicity than by specific actions of clearly identified terrorist groups. The SCO groups China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyztan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan..

|

|

|||||

© Uygur.Org 17.05.2006 18:41 A.Karakas |

|||||