|

On Old Silk Road,

Condos, Mosques and Ethnic Tensions

Stuart

Isett/Polaris, for The New York Times Stuart

Isett/Polaris, for The New York Times

In Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, Uighur peddlers

sold their wares at the Erdaoqiao

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

Published: March 16, 2004

RUMQI, China, March 12 ¡ª On a big public square

dominated by this city's huge gold-domed theater,

taxis honk their way through slushy, chaotic streets,

stopping to take on passengers laden with bundles of

walnuts, almonds, dates and dried plums purchased at

open stalls.

Others disembark to pray at one of a score of mosques

that dot the inner city, walking past vendors' tables

displaying DVD's with Arabic titles about the Persian

Gulf war of 1991.

The sidewalk diners at a nearby restaurant, biting

away at heavily spiced skewers of lamb kebab and

tucking into bowls of meaty stew, seem as though they

could have been chosen by casually throwing darts at a

map of Asia.

There are alluringly dressed women with black hair,

fair skin and striking blue eyes who look passably

Russian. There are men with heavily lined, tea-colored

faces and brush-thick mustaches who resemble Afghans.

There are Turkish-looking Uighurs in Muslim skullcaps

and robes and mid-length beards.

Most

are probably Chinese, though ¡ª no less than members

of the ethnic Chinese majority known as the Han, some

of whom, looking businesslike, are filing into a

pedestrian underpass nearby. Most

are probably Chinese, though ¡ª no less than members

of the ethnic Chinese majority known as the Han, some

of whom, looking businesslike, are filing into a

pedestrian underpass nearby.

"You've got to be able to speak a little bit of a lot

of languages in this work," said Ahat Imam, a burly,

dark-skinned man who operates a bank of telephones on

the sidewalk, where people call places throughout

China as well as the farthest corners of Central Asia.

"I can speak Uighur, a little Kazakh, a little Uzbek.

And when I see a customer, right away I can tell what

ethnic group he is from."

To

visit a city like this, the capital of China's far

western region of Xinjiang, is to be powerfully

reminded that this country is very much a work in

progress, a place where the center does not always

hold. To

visit a city like this, the capital of China's far

western region of Xinjiang, is to be powerfully

reminded that this country is very much a work in

progress, a place where the center does not always

hold.

Xinjiang's independence movements enjoy little of the

sympathy in the West that neighboring Tibet receives.

But this remote region, nearly as far from Beijing as

California is from Washington ¡ª along with Hong Kong

and, some would add, Taiwan ¡ª is every bit as much a

part of forces that are tearing at this country, much

as the former Soviet Union was sundered and as China

has been divided in the past.

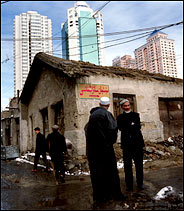

China is hastily redeveloping this frontier capital.

Sparkling office buildings and high-rise condos now

rise from streets that were dominated only a decade

ago by blocky, artless compounds dating from the

Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.

The rise of a new Urumqi (pronounced oo-ROOM-chee),

though, has barely papered over the ethnic and

religious cracks that run deep in this region, which

sits astride the ancient Silk Road. Islam reigned here

for 1,000 years, but it is under heavy pressure from

ethnic Chinese migration, breakneck development and

heavy-handed repression.

In today's Xinjiang, money, authority, power ¡ª and,

many Uighurs say, hope too ¡ª are all firmly in the

grasp of the ethnic Chinese, who arrive from poorer

areas of the country by the thousands every day to

seek their fortunes.

The restive Uighurs, a Central Asian ethnic group

common to this part of China and to the neighboring

former Soviet republics, are becoming an increasingly

voiceless minority in their own homeland.

Since the Sept. 11 attacks in the United States, China

has justified many of its policies in Xinjiang as part

of its own war on terror. Indeed, the Bush

administration has added Uighur separatist groups to

its lists of international terrorist organizations.

But the campaign of repression here, international

human rights experts say, has far older roots.

Scores of mosques have been razed and Uighur

literature burned. There have been forced "re-education"

campaigns of local religious leaders, many arrests of

people suspected of being separatists, and numerous

executions.

This region twice briefly enjoyed independence from

China in the 1930's and 1940's. Its dream of

self-determination was rekindled by the end of the

Soviet Union, when ethnic kinsmen in neighboring

republics, like Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, were given

independence.

Uighur demonstrations were put down with increasing

ferocity by the government, prompting ever bolder

actions by pro-independence groups.

The government has heavily reinforced security

throughout the province, reportedly installing hidden

cameras inside mosques and stepping up its

surveillance of students and others. Koranic schools

have been closed, and civil servants, teachers and

students have reportedly been forbidden to pray in

public.

Mickey Spiegel, a China expert at Human Rights Watch

in New York, said it was known that people had been

jailed for separatist activities. "The number of

executions is not known," she said. "I must say that

the information that is coming out of Xinjiang is

tighter than it has ever been."

Understandably, people in Urumqi speak guardedly with

strangers. "We give religious education to our

children at home," said Wang Yanqing, 53, a watchman

at a blue-tile-roofed Qing Dynasty mosque. "Islam is

not available in schools."

In one almost entirely Uighur neighborhood near the

center of town, on a frigid morning this week, Islamic

music rang out from an unseen sound box, and a cluster

of men danced playfully on a terrace.

Down the street, Tohti Hapiz, a Uighur blacksmith,

pulled red-hot iron bars from a crude street furnace

and beat them into meat cleavers with the help of two

apprentices. He said each would sell for about a

dollar.

Mr. Hapiz paused in reflection when asked what Urumqi

would be like in 20 years. "Uighurs don't have much to

do here, besides standing, smoking cigarettes,

drinking and selling things," he answered. "We are as

clever as the Han, but more and more this is becoming

their city. Meanwhile, the prisons are full of Uighurs."

|

Stuart

Isett/Polaris, for The New York Times

Stuart

Isett/Polaris, for The New York Times Most

are probably Chinese, though ¡ª no less than members

of the ethnic Chinese majority known as the Han, some

of whom, looking businesslike, are filing into a

pedestrian underpass nearby.

Most

are probably Chinese, though ¡ª no less than members

of the ethnic Chinese majority known as the Han, some

of whom, looking businesslike, are filing into a

pedestrian underpass nearby. To

visit a city like this, the capital of China's far

western region of Xinjiang, is to be powerfully

reminded that this country is very much a work in

progress, a place where the center does not always

hold.

To

visit a city like this, the capital of China's far

western region of Xinjiang, is to be powerfully

reminded that this country is very much a work in

progress, a place where the center does not always

hold.